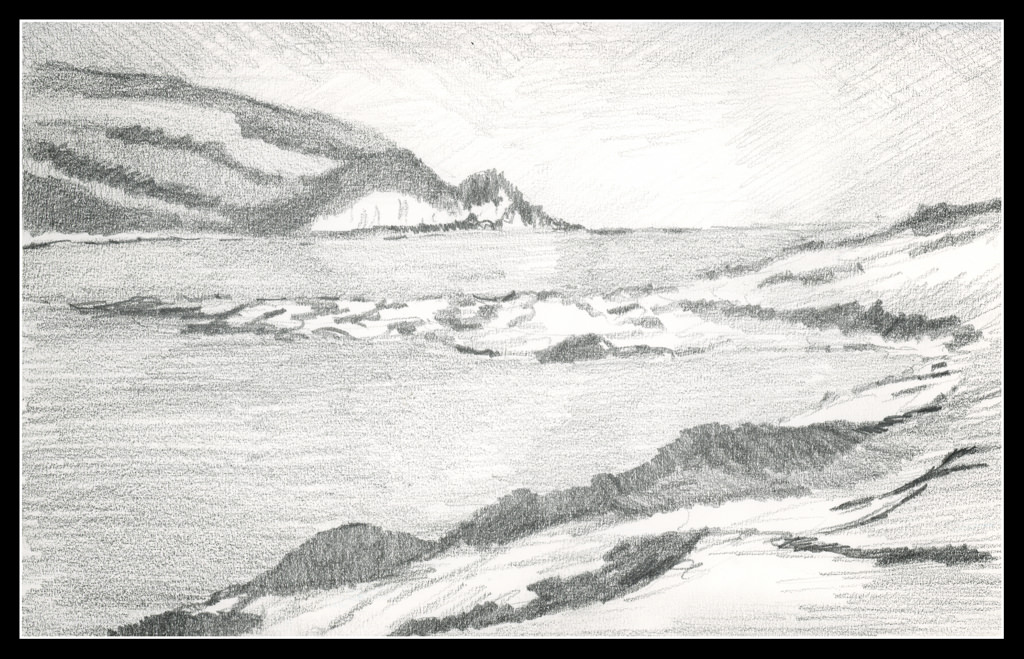

I think I am getting some of the points of this course and the usage of pencil to create value studies. First, I changed simply to an HB pencil and a smooth paper with a tiny bit of tooth. The bristol was too smooth a paper and the 2B and 4B pencils just smudged too easily despite my best efforts.

The teacher, Roberts, speaks of structure, rather than subject or detail, as the purpose of these drawings. This means masses of value, not picky details. The details can come in the painting, more so as it becomes larger. The value studies help sort out directing the eye to the point of interest.

The white cliff across the water is the focal point of the drawing, and, ostensibly, the painting. To lead the eye there I vignetted as one does in photography, but this time with graphite. The corners of the drawing are deliberately darker. A sort-of cloud or fog bank is light against the sky in the distance. I tried to use the pale reflection of the cliff in the water to draw the eye as well. Finally, I reworked the piles of sea weed and flotsam to aim the viewer toward the cliffs. The same can be said of the vegetation on the land above the cliffs.

I am beginning to get more comfortable with this approach to painting using a value study. 30 days of value studies is changing my eye and thought processes. Hopefully it will pay off in the future.