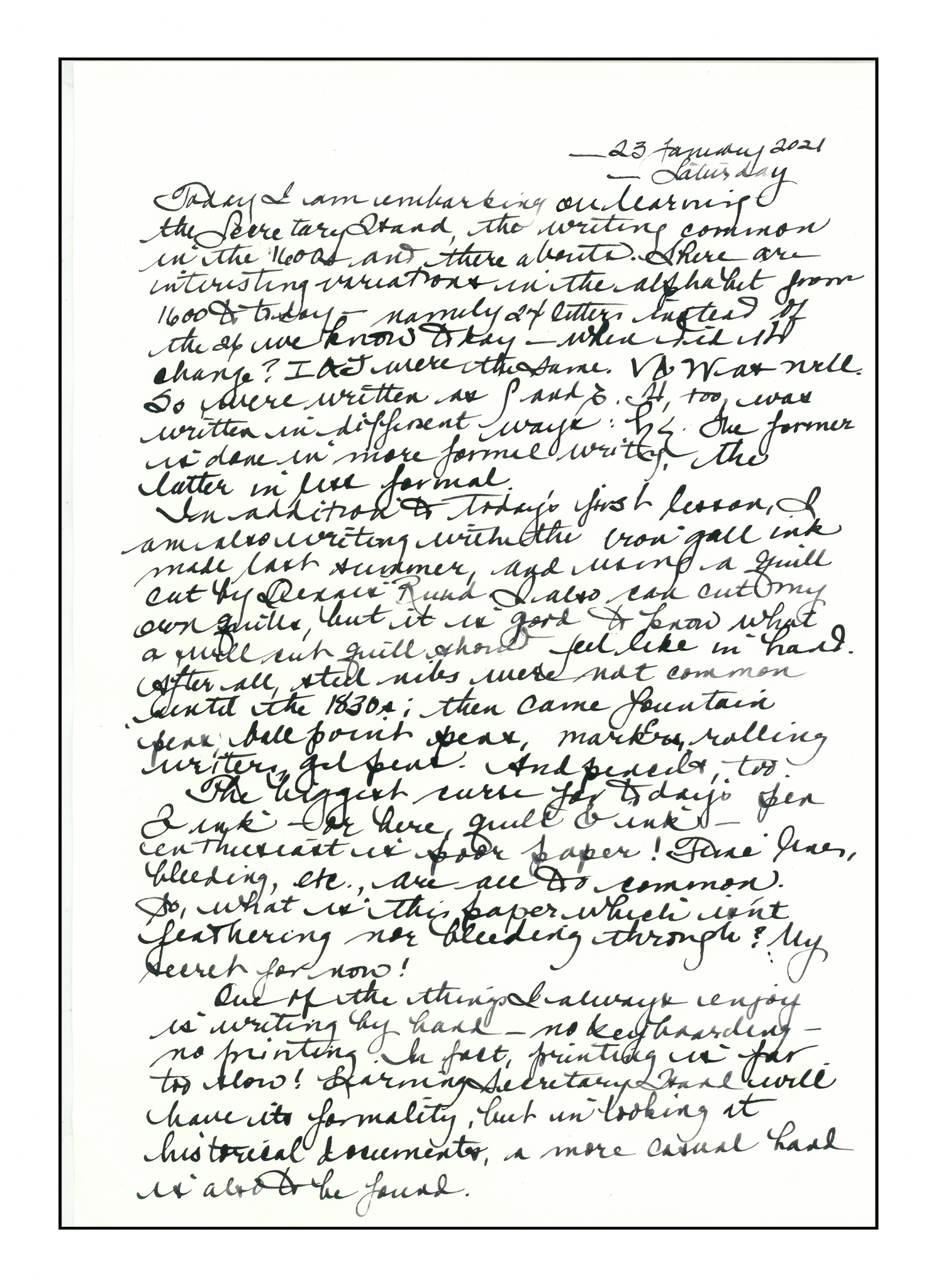

For the past year I have been keeping a journal – something I have done since I was 10 (I shred them, too!) – writing exclusively with goose / duck / turkey quill pens and iron gall ink, all made by myself.

Why do this? I like the act of writing. Just paper and ink and my thoughts or lists or complaints or observations. In this time period, just the daily usage of ink and quill has shown me and taught me a lot of things, things which are perhaps lost through time and the changes in technology. The fact is, too, I like to make things that I can use, and a quill pen and iron gall ink are proving to be two favorites.

Quills gave way from common usage in the 1830s when the metal nib came into easy manufacture and availability. Why not? Easier than cutting your own quill. Iron gall ink is easy to make if you have iron galls (though any plant material with tannin in it also works), and other ingredients available. It just takes time. Interestingly, powdered iron gall inks were available to the public, and apparently in common usage during the Revolutionary War by soldiers and others on the move. The powder was in packets, and all you did was sprinkle some ink on a surface, add water or wine or beer, and with your handy quill and a bit of paper, off you wrote.

Today’s treatise is about the Yncke itself. I’ve made multiple batches and have found out a few things that may have been common knowledge back when it was the only ink commonly available.

Observations

Iron gall ink is best used in small amounts, such as in an inkwell with a lid. The ink evaporates and particulate matter settles out with time. By keeping your ink in a sealed container – I use a mason jar with a lid – you keep it relatively fresh. It won’t evaporate although settling of the materials occurs.

I use a pewter inkwell, reputedly from the early 1800s, with a porcelain well. I keep it on a saucer as spills from iron gall ink stain anything easily. The porcelain is easily cleaned up. I replenish my ink every two or three days – a lot gets used up! Watching it disappear is rather fun.

When I replenish my ink, my choice of adding more ink or thinning it is really my first question. Experience has shown that through evaporation the ink becomes thicker and thus does not easily flow from the pen. I add water in a small amount, but after having read that one should use vinegar or spoilt wine or beer to keep the ink’s color strong, I have tried both. My experience is too limited at this point to make a more definitive statement that either works fine.

How do I know when I need to dilute my ink? I know when I can no longer write a long line of words with a single dip of the quill. The ink begins to blob up and becomes more viscous. If I find I can only write a word or two before the ink is very pale, I know that the first problem is the ink, not the quill. Then, I add a bit of water or vinegar or wine or beer, just a bit, and try writing again. If the flow improves, you are fine. I use a plastic pipette with a squeeze bulb because I can control the addition of liquid more easily than just pouring it into the well.

In using iron gall ink, I used to keep it in bottles with screw-on lids. Specifically, I used old fountain pen ink bottles. However, this ink is like a glue in some ways because the lids eventually stick to the bottle and become difficult to unscrew. Flying ink is not fun when you finally get that lid off! I store mine in 1 cup canning jars, the kinds with separate screw tops and lids, such as used in making jam or jelly. When I need more, if the lid is sticky, I can usually pry it off with a knife – slowly and gently! And I do it in the kitchen sink or with paper towels beneath the jar to catch any spillage. Clean any spills up immediately!!

Iron gall ink can spoil. I have had batches which developed a scummy surface on it, but it doesn’t seem to affect the quality of the ink. I just shake it up and mix it in. This seems to have occurred when I used water in making the ink. This last batch I made with some old wine, and the scum did not appear. I will say, too, that I like the smell of wine when I use fresh ink! It’s a nice addition.

Making it, as I said, takes time. There a numerous recipes on the internet. You can find my own commentaries on the ink by using the search feature. The recipe I use so far is as follows, and have been pleased with it, especially when I have made it with wine:

Receipt for Iron Gall / Oak Gall Ink

- Oak galls: 80 g.

- Distilled water / stale wine or beer / vinegar: 300 g.

- Ferrous Sulfate (I used ferrous sulfate heptahydrate): 50 g.

- Gum Arabic: 25 g.

Crush oak galls into small pieces or grind into powder using a spice or coffee mill. Place into jar and cover with 300 ml. of distilled water. Place in sunny window 3-7 days (depending on your life and schedule). I plan to do 3 as per the recipe from the Schoenberg Institute. After 3 days, there should be a dark murky liquid in the jar.

On Day 3, add 50 g. of Ferrous Sulfate to oak gall mixture; replace in sunny windows for another day. On Day 4 add the Gum Arabic and leave for another day. On Day 5, strain the liquid into a clean vessel and voila, ink!

My Check List For Using and Maintaining Iron Gall Ink

- Take the time to make iron gall ink. I think a week or two is best. Anticipate when you will need a new batch.

- Store unused ink in a closed container, such as a canning jar.

- Use a small amount of ink at a time as it easily evaporates and settles out.

- If your ink is thick, before adding more ink to your well, dilute first with small amounts of water, vinegar, stale wine or beer. Test with your quill. A pipette works well to transfer fresh ink or dilution liquid.

- Paper towels are excellent as blotting paper. I use toweling to blot a page before I turn it over, and I turn it over onto another sheet of toweling. Sadly, we no longer have blotters as daily items on our desks.

- Rinse your quill when done, and blot it dry. Have at least 3-4 quills available to use as they need to dry out between uses.

So, that is it for this posting. Hopefully it is of some use to those who would like to use iron gall ink and quills on a more regular basis. If you are just beginning to use these items, be patient and kind to yourself. Learning to write with a quill pen is not easy, and learning how to replenish the ink on your pen has its own quirks. We are used to pens where re-inking is not normal, but with both quills and metallic dip pen nibs, there is a pattern and rhythm to getting the right amount of ink on your pen. Once you master it – and it shouldn’t take long – you might find yourself quite happy with your new skills!