Warning! A very long and windy read. Get your coffee or tea, put your feet up, and follow along . . .

I was going through my archives thinking I might have written something up about the last time I did indigo dyeing, but I guess I didn’t. So, we shall begin sort of at the beginning!

Indigo is a wonderful dye, and I have used a variety of methods to extract the blue color. Over the 40-odd years I have been dyeing, I have used urine, sulfuric acid, and finally a kit. The kit is the best and easiest and least time consuming or hazardous.

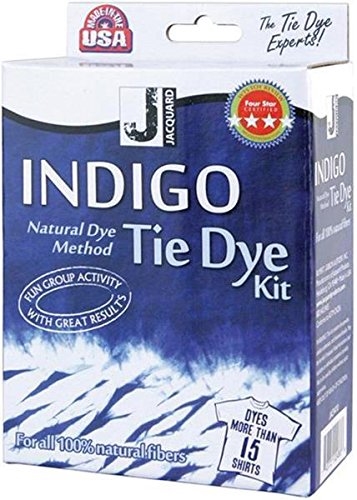

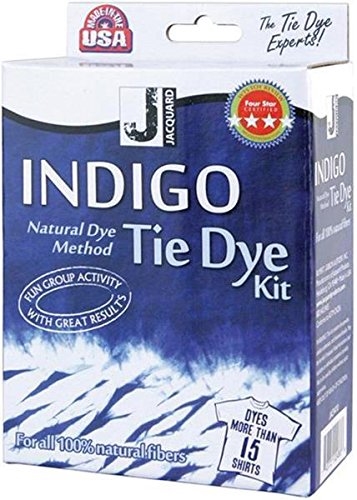

Indigo is a plant that is used to dye fabrics of all kinds – plant and animal fibers, cotton and silk – for centuries. In the dye bath, it is a disgusting greenish yellow – not like spring’s new leaves, but a pukey army green. It also doesn’t smell appetizing. To create a dye bath, you can use all sorts of chemicals, save your urine, or buy a simple kit. I like the kit that is available from Jacquard – small, easy, convenient. For the bulk dyer, this would not be a good buy, but for a small once-in-awhile dyer, it is great. You can buy it from Dharma Trading, Amazon, or KnitPicks, to name a few places.

Last year, my MIL Judy came by and we did a bunch of indigo dyeing. We dyed yarn and fabric, doing flammegarn and batik as well.

Flammegarn dyeing involves taking a skein of white yarn and tying off areas of it. The binding material acts as a resist. The yarn is then submerged into the dye bath, and the color is taken up. Multiple colors can be used, and multiple dippings. The result is a randomly mottled yarn. I believe this is originally a Scandinavian technique – the name implies such – but I am sure other cultures have done it as well.

Batik is the use of a resist on fabric to prevent colors from dyeing the fabric. Wax is the traditional resist. Multiple layers and colors can be built up, and complex patterns can be created. You can apply the wax with a brush or a stamp, a stencil, or a djanting tool.

Removing the string resist in flammegarn is easy, but removing the wax resist in batik is problematic. Removing the wax from the fabric is a chore. Boiling or near-boiling water is needed to melt the wax. Once that is done, by dipping the cloth multiple times into boiling water, it is then further treated. It can be sent to the dry clearer and chemical solvents used (ick!), or you can iron it between layers of newsprint using a very hot iron to remove the last of the wax. I have always done this, but it never really did the trick. There was always a residual coating of wax that never seemed to leave the fabric, even after multiple washings in hot water, in the sink, in the washing machine, and ironing. However, I have now discovered how to remove wax quite easily!

First, though, let’s back track a bit. Judy took a brush and a lot of wax to her fabric (cotton or linen or a mix thereof we are not sure). Here is her material, dyed and waxed and now awaiting wax removal. This material is very stiff, and if you want to crumple it up in a ball, forget it. Instead, you really have to fold it! The wax then cracks and falls off if it is really thick. I don’t think you want to take it to your sewing machine in this condition! The fabric measures about 40″ wide and about 1.5 yards long.

Yesterday morning, Josh and I worked on getting the wax out. Below you can see what we did. Josh pulled out his brew rig, which runs on natural gas from our home, and set up my 4-gallon pot with water on the middle burner. Behind Josh is his 15 gallon hot liquor tank that he uses to boil water in beer making. It has a temperature gauge on it along with a spigot to which you can attach a hose. You don’t want to lift this boiling water, so he uses the spigot and hose to move hot water to his other kettles when brewing. This set up worked out really well for us as from the liquor tank we could easily and safely move the boiling water into the galvanized wash tub you see next to him. (All that red stuff behind the brew rig are car panels for the 818S!)

The 4-gallon kettle took minutes to bring to a boil, and so we moved it into the galvanized tub. The indigo-dyed cloth was submerged, and stirred. The wax began to melt out of the cloth, and some of the indigo dye bled out. I used wooden dowels and spoons to lift the material in and out of the water, stirring it and mushing it around.

Here is a close-up of the spoon, fabric, melting wax and hot water. Water dripped and splashed into the galvanized tub – I used that to scrub out the dirt before we added the water from the liquor tank. Pretty efficient, eh?

After several dippings and stirrings, the fabric was removed from the 4-gallon kettle. Wax and murky water remained behind. You can see the liquid wax on the top of the water, and the hardened wax on the sides of the pot. It is interesting to note that the water has a greenish cast – water when you are dyeing indigo is also green. The blue color of indigo does not occur until the fabric or yarn is pulled out of the dye bath and exposed to oxygen.

Using the dowel and spoon, the fabric was lifted out of the pot and allowed to drip into the 4-gallon kettle. Here are the remains of the wax after the water was discarded. This was taken the next morning after the water had cooled and the wax had risen to the surface of the water. You don’t want to be pouring this stuff down your pipes!

The secret for easy wax removal is now revealed! Read on, oh fans, read on!

The wash tub was then filled with hot water from the liquor tank – 15 gallons of boiling water. About 1/4 cup of dish soap (Dawn concentrate) was added to the water and stirred into the water. And that is the secret! The soap emulsifies the wax and allows it to be dispersed into the water or something.

The fabric wanted to float to the surface of the water, even after squishing out the air bubbles. I stirred and lifted the fabric again, making sure to mix it all up really well in the soapy water. Interestingly, no suds developed. Before sealing it to cool, I weighted the fabric down in the tub with some bricks to ensure it did not rise to the surface and collect any wax which had been removed. Then, we sealed if for the night! We used the wheels from the donor WRX. Our goofy dogs wanted to taste the soapy water, and I wasn’t inclined to let them indulge.

The wash tub and tires sat over night, to let the water to cool. The bricks would prevent the fabric from floating and getting re-waxed. The next morning, the tires were removed, and this is what we saw! No wax on the cold water’s surface!

I was really quite surprised. Never have I had such an easy time removing wax from fabric before. I pulled the material out of the tub, placing it into a bucket, and taking it to the kitchen sink. I wore some nitrile gloves (I didn’t want to turn blue) and rinsed and squeezed the fabric in the sink. From there, once the water was clear, the whole thing was carted to the washing machine, loaded in with hot water and laundry soap. When the cycle was done, into the dryer for the final step of ridding the batik of wax.

I was really quite surprised. Never have I had such an easy time removing wax from fabric before. I pulled the material out of the tub, placing it into a bucket, and taking it to the kitchen sink. I wore some nitrile gloves (I didn’t want to turn blue) and rinsed and squeezed the fabric in the sink. From there, once the water was clear, the whole thing was carted to the washing machine, loaded in with hot water and laundry soap. When the cycle was done, into the dryer for the final step of ridding the batik of wax.

And the washer and dryer are perfectly fine, thank you very much.

The fabric is now supple, easily crumpled into a ball, and ready to be sewn into a skirt of some sort. I think it would make a great sarong! Here are more pictures of the final cloth – all it is needs is a bit of ironing and styling.

A close up shows how the wax cracks and the dye seeps in, as well as how it colors areas with less wax. The thicker the wax, the less likely the indigo or dye is to seep in. Because the wax was thickly applied, cracks easily develop. Areas where thinner wax is applied and not worked into the fibers are more likely to take some dye, albeit less intensely.

Finally, a closer shot showing the weave of the fabric – and I think it is linen! The texture of the weave is more irregular that cotton, but the fine weave of the fabric made me wonder.

And, at last, this beautiful indigo-dyed linen fabric is crumpled up and ready for its next iteration!