As Jane Austen wrote in Pride & Prejudice:

“I am afraid you do not like your pen. Let me mend it for you. I mend pens remarkably well.”

“Thank you – but I always mend my own.”

Austen is discussing the quill pen in particular – a pen made from the feather of a bird, usually a goose, and cut with a pen knife. The ink is most likely iron gall ink, made at home or sold in penny jars. Pre-cut quill pens could also be bought, perhaps well made or not, but certainly could be customized to one’s own liking. It is from this particular section of Pride & Prejudice that I decided I could “mend my pen” to my liking as it got worn with use.

First, let us consider what writing with a quill pen entails. It means getting a feather, preferably a long feather from a goose’s wing, a first or second pinion about 14-16 inches long. From there, the feather is aged before cutting – reportedly a year – or cured with heat, or “clarified” after soaking overnight in water that might have alum added to it. Then it is trimmed with all feathery parts are removed. The end of the feather that attached to the bird is the part which becomes the nib. It’s a complex process to learn, but easy enough once you get your mind around the steps and shape you need. As always, practice makes perfect – but even an imperfectly cut quill pen can write quite well. I speak from experience.

To cut a quill, you need to soak it in water and then heat treat it to “clarify” it – making it hard enough to handle the cutting process. This video shows you this step:

YouTube, of course, has a number of videos about it. Some are good and some are absolutely ridiculous. Here is a good one – he has already clarified his feather:

And this is basically what you do all over again when you “mend your pen”!

Why mend? Why re-trim and shape a feather quill pen? For one thing, quill pens are like anything – some you really like! I have one that fits perfectly in my hand and is a daily writer. Others are not as comfortable, some quills are narrower in diameter and less comfortable; wider in diameter and uncomfortable for lack of familiarity. All can write beautifully and I, the user, simply adapt to each one. However, quills do become a bit messy if used regularly and a good mending can refresh them. As well, quill pens require rotation – the nib becomes soggy from the ink, and need to dry out. My inkwell from the early 1800s has 4 holes in it, to hold 4 pens, so I can cycle through them (not that I do!).

When I choose to mend a pen, I follow a protocol that seems to work for me. Here are the steps.

- Test the pen by using it. What is the problem?

- Soggy pen? Too wide? I usually begin by re-cutting the very end of the pen off to create a new writing surface. Test the pen. Problem solved? Go no further.

- If the pen is still not writing with a clarity of your liking, sometimes you just need to shave off a bit of the top and bottom of the nib as done in the video. This can help sharpen a nib. Test again.

- After the above trimming, you may want to make your nib a bit more narrow, so shape the sides of the pen. I do this a little at a time, carefully, and test the pen until it is to my liking.

- Does the pen fail to carry ink beyond a few words? It could be the slit in the pen nib needs to be re-cut. When this occurs, I usually have trimmed the nib using the above steps before re-cutting the slit. The slit is important for ink flow; without it your ink can blob out all at once and that is not a nice thing to have on your paper!

- Is your pen, after trimming, writing rough? If so, I find that 3M 2000 grit wet sand paper helps. Write on the sand paper, practicing the marks you make when using cursive.

The tools I use for making and mending my pens are a few. They include

- Toenail trimmer

- Quill knife – a pen knife as seen in the 2nd video

- Xacto knife

- Self-healing mat

- 3M 2000 grit sand paper

- Small tool to clean out inside of quill

Here is a good video about tools used to cut a quill, as well as cutting the quill itself:

You don’t need all these things – the differences of quill cutting varies, as you can see, from the above videos.

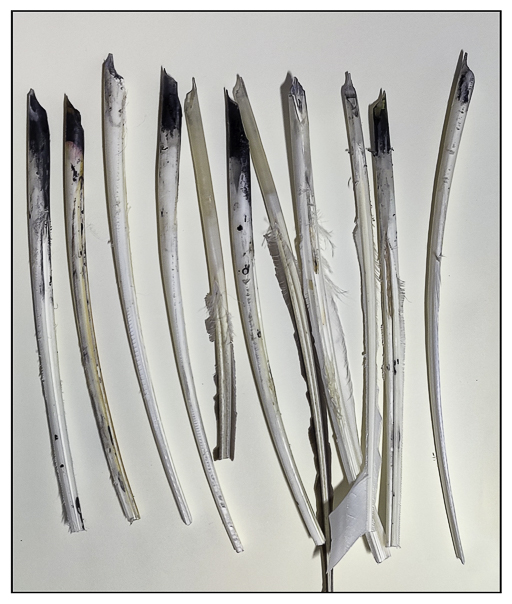

So, today I mended about 7 pens and cut 5 more, two of which were failures. I threw an old quill pen out as it was done in, and my mending attempts only made it worse. I saved my favorite pen and fixed a bunch and made some new ones. Not a bad few hours spent in the sunny patio! I now have 11 usable quills for my daily jottings.

And a close up of the nibs – some are quite inky!

Hope this helps you realize that your old feather quill pen can still be used with a bit of TLC! If they did it in the Regency period, you can still do it in the 21st century.